The research on the burials in crypts is usually related to two branches of science – archaeology and physical anthropology. Looking from the perspective of archaeology, crypt archaeology1Margaret Cox, Paul Kneller, “Crypt Archaeology: An Approach”, IFA paper, no. 3, [accessed 10.09.2018], [electronic], available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.112.5229&rep=rep1&type=pdf; Dario Piombino-Mascali, et al., “Crypt Archaeology: Preliminary Investigations in the Basilian Church of the Holy Trinity of Vilnius, Lithuania”, Medicina Historica, 2017, vol. 1, no. 2, p. 128-130. often falls in the fields of burial archaeology and church archaeology.

Burial archaeology and bioarcheology. Burial archaeology, in other words, the study of burial sites, is one of the oldest and most significant areas of archaeological science. It is closely related to physical anthropology3For example, in the periodical publication Archeologiniai tyrinėjimai Lietuvoje the data on different anthropological investigations is provided from the 1970s , and since 1982 it has been done on a regular basis.. Nowadays physical anthropology is already perceived as a part of bioarcheology (See more: Lithuania. Bioarcheology), the interdisciplinary sphere, which investigates eco-facts (organic material: plant and insect remains, animal and human bones, etc.) discovered in archaeological objects and capable of providing valuable information to archaeological science2For more see Interacting with the Dead. Perspectives on Mortuary Archaeology for the New Millennium, eds. Gordon F. M. Rakita, et al., University Press of Florida, 2008; Sarah Tarlow, Liv Nilsson Stutz, The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Death & Burial, Oxford University Press, 2013..

Church archaeology. Archaeology of churches or Christian religious places and buildings is a field of archaeology that studies Christian church heritage4Rimvydas Laužikas, “Church and Monastery Archaeology”, A Hundred Years of Archeological Discoveries of Lithuania, eds. Gintautas Zabiela, Zenonas Baubonis, Eglė Marcinkevičiūtė, Vilnius: Lietuvos archeologijos draugija, 2016, p. 474.. Modern archaeological investigations of churches differ significantly from earlier (traditional) “church excavations” conducted in the past. Its contemporary research subject is broad and complex (buildings, their surroundings, sites of old churches, burials, monuments, religious requisites, etc.) noted for a variety of sources (material, written, iconographic, etc.) and requiring the use of methods of different branches of science (archaeology, history, history of arts, architecture, etc.)5Warwic Rodwell, Church Archaeology, London: B. T. Batsford Ltd/English Heritage, 1989, p. 13-14..

Archaeology of historic times. For a long time archaeologists were interested almost exclusively in prehistory. Much less attention was paid to the Middle Ages, and the data of the investigations carried out in earlier periods often remained only in archaeological research reports. This is also true for the investigations of burial monuments. This situation can be observed not only in Lithuania. In recent decades, however, the situation has changed in essence: having perceived a scientific potential of the investigations of late historical burials, the archaeologists of the Western countries started focusing not only on the “underground” objects (including burials discovered in crypts) but also on the ones that are present “on the ground” (tombstones, chapels, columbaria, mausoleums and other architectural buildings). However, it is noted that archaeological investigations of historical or post-medieval burials still lack an integrated approach, and therefore it is not always possible to disclose the phenomenon of a burial as a practical (dealing with dead bodies) and cultural (ideological, social and cultural contexts) action6Sarah Tarlow, “Introduction: Death and Burial in Post-medieval Europe”, The Archaeology of Death in Post-medieval Europe, ed. Sarah Tarlow, Warsaw/Berlin: De Gruyter Open Ltd, 2015 p. 1-18; for more see Mike Parker Pearson, The Archaeology of Death and Burial, Pheonix Mill: Sutton Publishing, 2003; Kultura funeralna: Elit Rzeczypospolitej od XVI do XVIII wieku na terenie Korony i Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego. Próba analizy interdyscyplinarnej, ed. Anna Drążkowska, Toruń: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika, 2015.. The study of burials can provide knowledge of the burial traditions of a certain period, as well as characterize the society of that particular time.

Justina Poškienė

Lithuania. Bioarcheology

| 1. | ↑ | Margaret Cox, Paul Kneller, “Crypt Archaeology: An Approach”, IFA paper, no. 3, [accessed 10.09.2018], [electronic], available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.112.5229&rep=rep1&type=pdf; Dario Piombino-Mascali, et al., “Crypt Archaeology: Preliminary Investigations in the Basilian Church of the Holy Trinity of Vilnius, Lithuania”, Medicina Historica, 2017, vol. 1, no. 2, p. 128-130. |

| 2. | ↑ | For more see Interacting with the Dead. Perspectives on Mortuary Archaeology for the New Millennium, eds. Gordon F. M. Rakita, et al., University Press of Florida, 2008; Sarah Tarlow, Liv Nilsson Stutz, The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Death & Burial, Oxford University Press, 2013. |

| 3. | ↑ | For example, in the periodical publication Archeologiniai tyrinėjimai Lietuvoje the data on different anthropological investigations is provided from the 1970s , and since 1982 it has been done on a regular basis. |

| 4. | ↑ | Rimvydas Laužikas, “Church and Monastery Archaeology”, A Hundred Years of Archeological Discoveries of Lithuania, eds. Gintautas Zabiela, Zenonas Baubonis, Eglė Marcinkevičiūtė, Vilnius: Lietuvos archeologijos draugija, 2016, p. 474. |

| 5. | ↑ | Warwic Rodwell, Church Archaeology, London: B. T. Batsford Ltd/English Heritage, 1989, p. 13-14. |

| 6. | ↑ | Sarah Tarlow, “Introduction: Death and Burial in Post-medieval Europe”, The Archaeology of Death in Post-medieval Europe, ed. Sarah Tarlow, Warsaw/Berlin: De Gruyter Open Ltd, 2015 p. 1-18; for more see Mike Parker Pearson, The Archaeology of Death and Burial, Pheonix Mill: Sutton Publishing, 2003; Kultura funeralna: Elit Rzeczypospolitej od XVI do XVIII wieku na terenie Korony i Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego. Próba analizy interdyscyplinarnej, ed. Anna Drążkowska, Toruń: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika, 2015. |

Sources of Illustrations:

| 1. | Photograph by Jan Bułhak, [“Vilniaus katedros centrinė nava. Požemių kasinėjimai”], 1931 // in: Lietuvos dailės muziejus (Lithuanian Art Museum), LDM Fi-282 (in: Lietuvos integrali muziejų informacinė sistema [LIMIS], [accessed 07.10.2019], [electronic], available at: www.limis.lt/greita-paieska/perziura/-/exhibit/preview/20000002648344?s_id=mUxzUfnS0SCubm3M&s_ind=1&valuable_type=EKSPONATAS). |

| 2. | In: Kultūros paveldo centro archyvas (Cultural Heritage Centre). |

| 3. | In: Kultūros paveldo centro archyvas (Cultural Heritage Centre). |

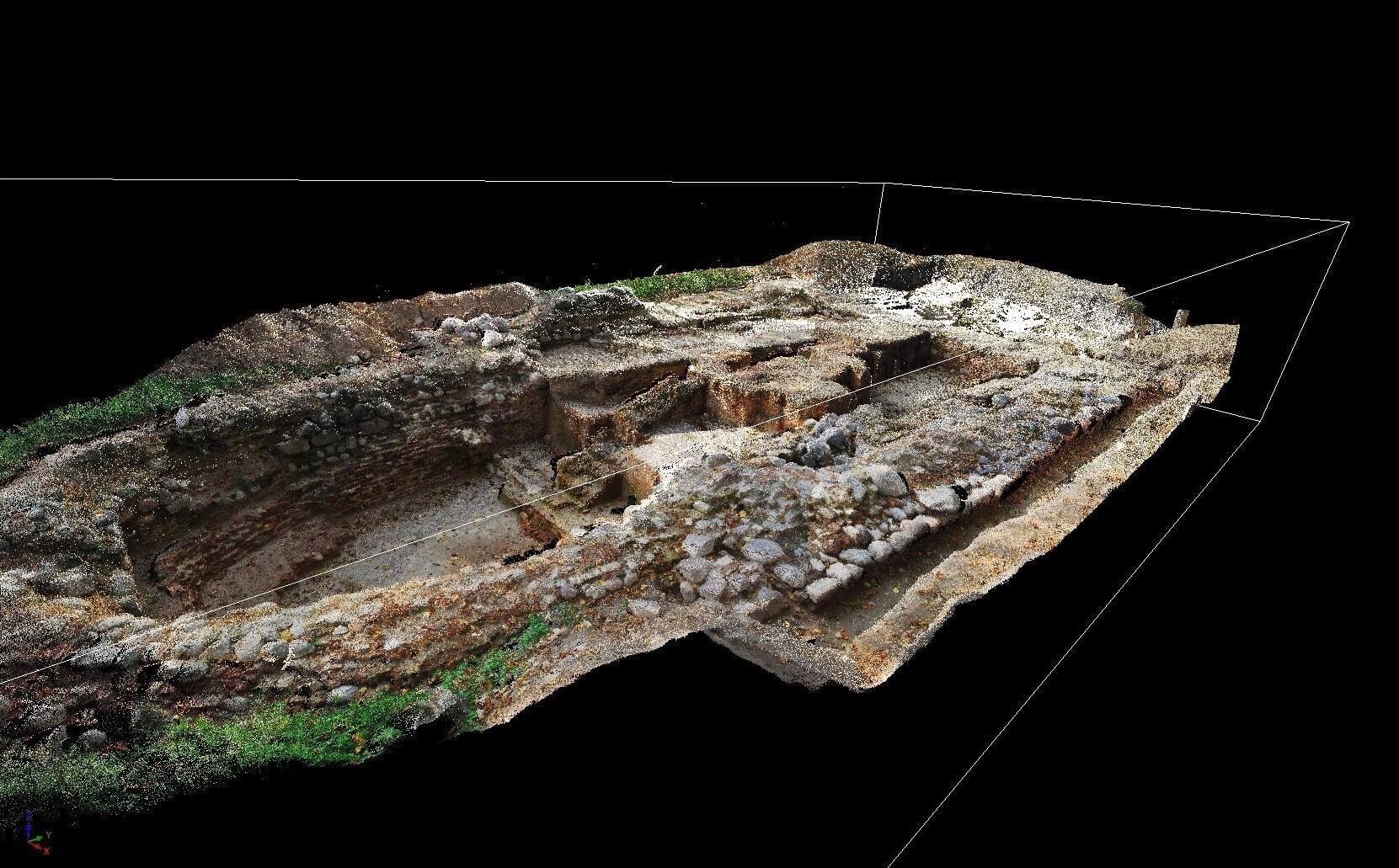

| 4. | Photograph by Rimvydas Laužikas, [“Dubingių bažnyčios vieta po archeologinių tyrimų”], 2007 // in: Rimvydas Laužikas’ personal collection. |

| 5. | Author Ramūnas Šmigelsgas, [“Dubingių bažnyčios 3D”], 2007 // in: Albinas Kuncevičius’ personal collection. |

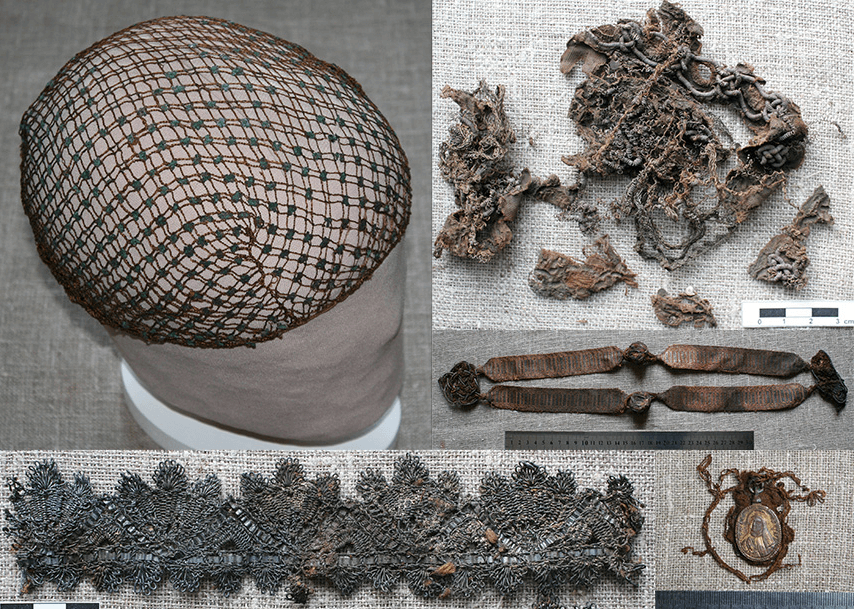

| 6. | Author Ramūnas Šmigelsgas, [“Dubingių bažnyčios vieta ir ten rasti radiniai”], 2007 // in: Albinas Kuncevičius’ personal collection. |

| 7. | Photograph by Olegas Fediajevas, 2008 // in: Olegas Fediajevas’ personal collection. |

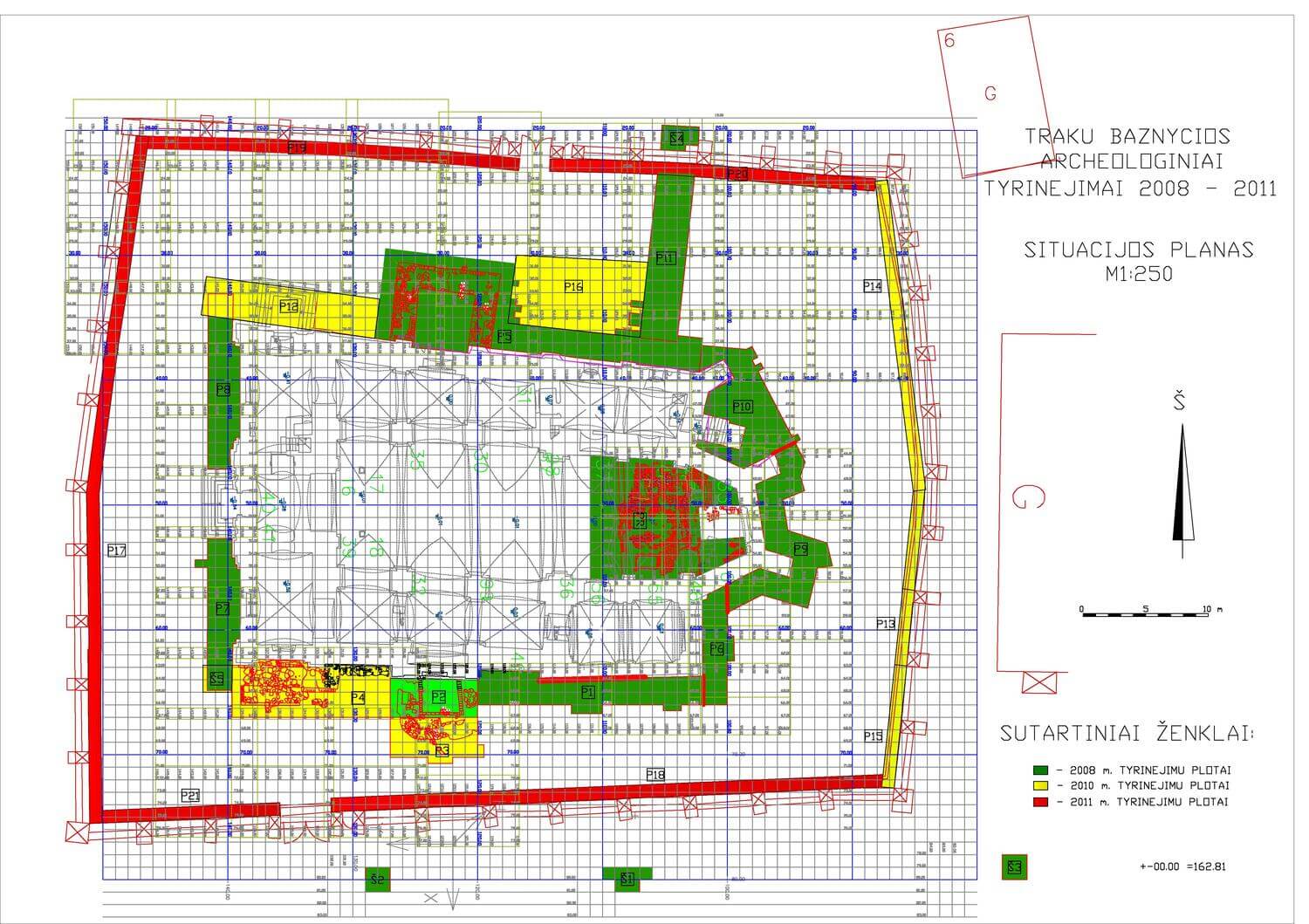

| 8. | Author Olegas Fediajevas, “Trakų bažnyčios archeologiniai tyrinėjimai 2008–2011. Situacijos planas”, 2011 // in: Olegas Fediajevas’ personal collection. |

| 9. | Photograph by Olegas Fediajevas, 2008 // in: Olegas Fediajevas’ personal collection. |